Romeo and Juliet

By Ifeoma Egbogah in visualization, blog, text analysis

September 22, 2024

Story Structure of Romeo and Juliet: A Tidy Analysis

Using this week’s #TidyTuesday dataset, we are exploring dialogue in Shakespeare plays. The dataset this week comes from shakespeare.mit.edu (via github.com/nrennie/shakespeare) which is the Web’s first edition of the Complete Works of William Shakespeare. The site has offered Shakespeare’s plays and poetry to the internet community since 1993.

Dialogue from Hamlet, Macbeth, and Romeo and Juliet are provided for this week.

I will be analysing the story structure of Romeo and Juliet. This is analysis is inspired by David Robinson’s “Examining the arc of 100,000 stories: a tidy analysis”.

“Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?”

With love’s light wings did I o’er-perch these walls; For stony limits cannot hold love out."

— (Romeo, Act 2 Scene 2)

Figure 1: AI Generated Art

Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet is one of his most known works. It is a tragic love story set in Verona, Italy. It revolves around two young lovers, Romeo Montague and Juliet Capulet, who come from feuding families.

Key Events:

- Meeting at the Ball: Romeo sneaks into a Capulet ball, where he meets Juliet, and they instantly fall in love, unaware of each other’s family ties.

- The Balcony Scene: Later that night, Romeo visits Juliet’s balcony, and they confess their love for each other, deciding to marry in secret.

- Secret Marriage: With the help of Friar Lawrence, Romeo and Juliet marry the next day.

- Tybalt’s Death: Tensions rise between the families. Romeo’s friend Mercutio is killed in a fight with Juliet’s cousin Tybalt. Soon after, Romeo kills Tybalt, Juliet’s cousin, in a duel and is banished from Verona.

- Tragedy: As Juliet faces an arranged marriage to Paris, she turns to Friar Laurence, who gives her a potion to fake her death. Romeo, unaware of the plan, hears of Juliet’s “death” and, devastated, buys poison. He goes to her tomb, drinks the poison, and dies beside her. Juliet awakens, finds Romeo dead, and kills herself with his dagger.

- Reconciliation: Their deaths finally reconcile their feuding families, highlighting the futility of hatred.

The play explores themes of love, fate, and conflict.

Explore Data

Our analysis goal is to analyse the story structure quantitatively looking at words that tend occur at various points in the story particularly words that occur at the beginning, middle and end.

The tidytext package is used to unnest the dialogue of the characters into a tidy format with one word per line.

Shakespeare’s Language: The Pronouns that Define Romeo and Juliet

The words Thou, Thy, and Thee dominate the dialogue in Romeo and Juliet. These classic pronouns give the play its timeless, poetic feel, transporting us back to Shakespeare’s era

David Crystal writes in The Cambridge Encyclopedia of English that by Shakespeare’s time, you “was used by people of lower rank or status to those above them (such as ordinary people to nobles, children to parents, servants to masters, nobles to the monarch), and was also the standard way for the upper classes to talk to each other. […] By contrast, thou / thee were used by people of higher rank to those beneath them, and by the lower classes to each other; also in elevated poetic style, in addressing God, and in talking to witches, ghosts and other supernatural beings.”\

top_word <- romeo_juliet_token %>%

count(word, sort = TRUE) %>%

top_n(25) %>%

mutate(word = fct_reorder(str_to_title(word), n)) %>%

ggplot(aes(n, word)) +

geom_point_blur(aes(y = word, size = n, blur_size = n), colour = "#B32B9E",

blur_steps = 3,

show.legend = FALSE) +

geom_segment(aes(x = n, xend = 0, y = word, yend = word), linewidth = 1, colour = "#B32B9E") +

scale_blur_size_continuous(range = c(1, 5)) +

scale_size(range = c(2, 5)) +

theme(plot.background = element_rect(fill = "#EBD8EC"),

panel.background = element_rect(fill = "#EBD8EC")) +

labs(x = "Word Count",

y = "Words",

title = "Top 25 Spoken Words in Romeo and Juliet")

## Selecting by n

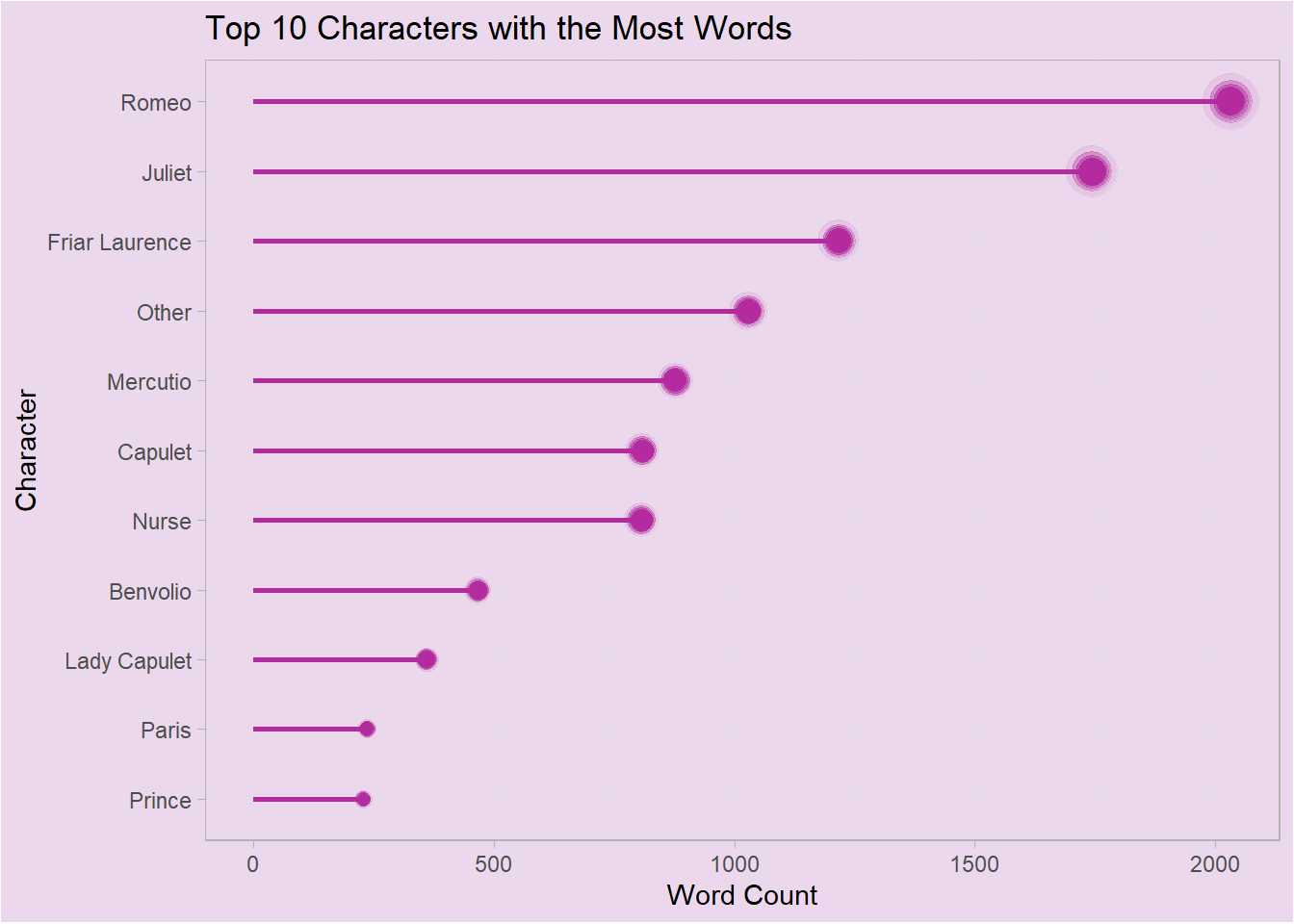

The Voices that Shape the Tragedy

No surprises here—being the title characters, Romeo and Juliet have the most words in the play. Their words carry the heart of the story, driving the romance and tragedy forward.

character <- romeo_juliet_token %>%

select(character) %>%

mutate_if(is.character, as.factor) %>%

mutate(character = fct_lump_n(character, 10)) %>%

count(character, sort = TRUE) %>%

mutate(character = fct_reorder(character, n)) %>%

arrange(desc(n)) %>%

mutate(id = row_number()) %>%

ggplot(aes(n, character)) +

geom_point_blur(aes(y = character, size = n, blur_size = n), colour = "#B32B9E",

blur_steps = 3,

show.legend = FALSE) +

geom_segment(aes(x = n, xend = 0, y = character, yend = character), linewidth = 1, colour = "#B32B9E") +

scale_blur_size_continuous(range = c(1, 5)) +

scale_size(range = c(2, 5)) +

theme(plot.background = element_rect(fill = "#EBD8EC"),

panel.background = element_rect(fill = "#EBD8EC")) +

labs(x = "Word Count",

y = "Character",

title = "Top 10 Characters with the Most Words")

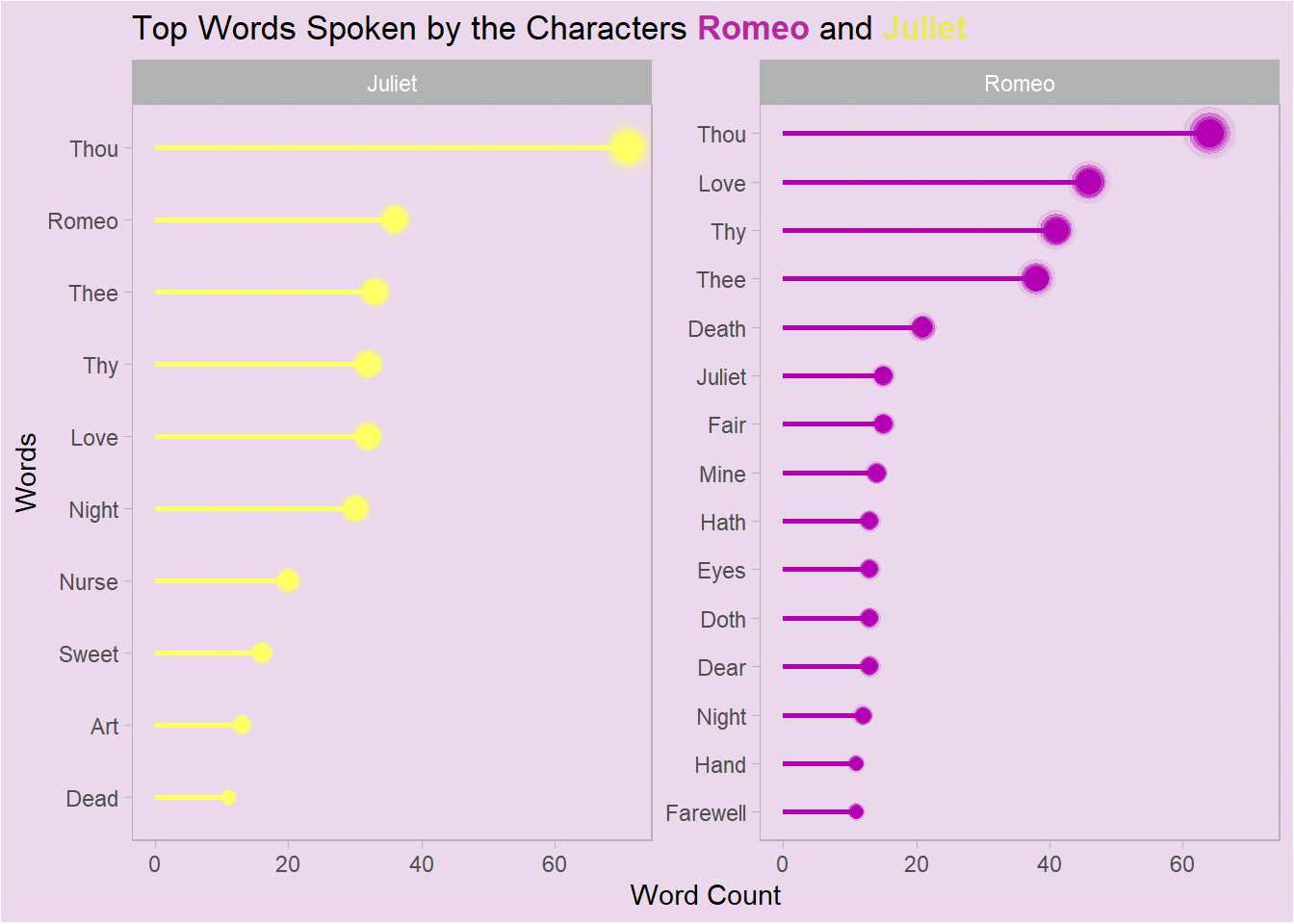

Words of Love: The Most Spoken Words by Romeo and Juliet

Why, then, O brawling love! O loving hate!

— (Romeo, Act 1 Scene 1)

Art thou not Romeo and a Montague?

— (Juliet, Act 2 Scene 2)

Juliet’s most frequent words in the play are Thou, Romeo, and Thee, reflecting her deep connection to her lover. Meanwhile, Romeo often uses Thou, Love, and Thy, highlighting his passion and devotion.

chac <- c("Romeo", "Juliet")

romeo <- romeo_juliet_token %>%

count(word, character, sort = TRUE) %>%

filter(character %in% chac) %>%

top_n(25) %>%

mutate(word = reorder_within(str_to_title(word), n, character)) %>%

ggplot(aes(n, word, fill = character, colour = character)) +

geom_point_blur(aes(y = word, size = n, blur_size = n),

blur_steps = 3,

show.legend = FALSE) +

geom_segment(aes(x = n, xend = 0, y = word, yend = word), linewidth = 1) +

scale_blur_size_continuous(range = c(1, 5)) +

scale_size(range = c(2, 5)) +

facet_wrap(~character, scales = "free_y") +

scale_y_reordered() +

scico::scale_color_scico_d(palette = "buda", guide = "none", direction = -1) +

scico::scale_fill_scico_d(palette = "buda", guide = "none", direction = -1) +

labs(x = "Word Count",

y = "Words",

title = "Top Words Spoken by the Characters <span style = 'color:#B32B9E;'>**Romeo**</span> and <span style = 'color:#EAE767;'>**Juliet**</span>") +

theme(plot.background = element_rect(fill = "#EBD8EC"),

panel.background = element_rect(fill = "#EBD8EC"),

plot.title = element_textbox())

## Selecting by n

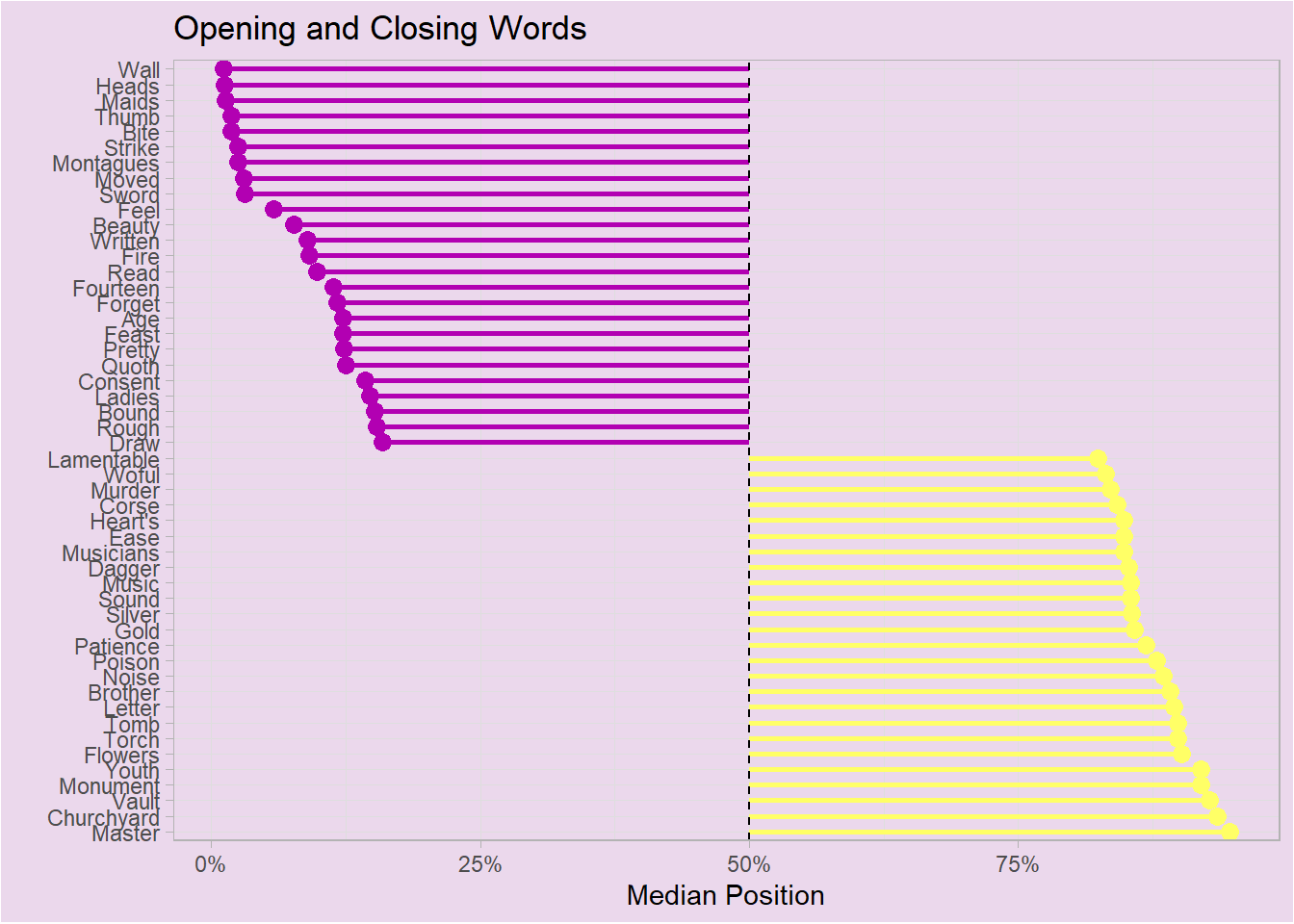

Words at the Beginning and End of story

Opening Words

Words like wall, heads, maids, thumb, bite, swords, strike, Montagues, and fray set the stage for the play’s opening tension. These words paint a picture of brewing conflict and public confrontation in the streets of Verona. The household servants of the feuding Montagues and Capulets are at the heart of this chaos, where minor provocations—like biting a thumb—quickly escalate into violent brawls. The word wall may symbolize the deep physical and social divide between the two families, foreshadowing the tragic love story that will unfold amidst this backdrop of rising violence.

word_averages <- romeo_juliet_token %>%

mutate(word_position = row_number()/n()) %>%

group_by(word) %>%

mutate(median_position = median(word_position),

number = n())

top_and_bottom <- word_averages %>%

filter(number > 4) %>%

distinct(word, median_position, number) %>%

arrange(desc(median_position))

# Get the top 25

top_25 <- top_and_bottom %>%

head(n = 25)

# Get the bottom 25

bottom_25 <- top_and_bottom %>%

tail(n = 25)

# Combine the two

combined <- bind_rows(top_25, bottom_25)

chart<- combined %>%

mutate(direction = ifelse(median_position < .5, "Beginning", "End")) %>%

ggplot(aes(median_position, fct_reorder(str_to_title(word), -median_position), color = direction)) +

geom_point(size = 3) +

geom_errorbarh(aes(xmin = .5, xmax = median_position), height = 0, linewidth = 1) +

geom_vline(xintercept = .5, lty = 2) +

scale_x_continuous(labels = scales::percent_format()) +

scico::scale_color_scico_d(palette = "buda", guide = "none") +

theme(plot.background = element_rect(fill = "#EBD8EC"),

panel.background = element_rect(fill = "#EBD8EC"),

plot.title = element_textbox()) +

labs(x = "Median Position",

y = "",

title = "Opening and Closing Words",

colour = " ")

Closing Words

Words like torch, flowers, monument, youth, tomb, watch, vault, and churchyard mark the somber shift from the public conflicts of the play to its private, mournful conclusion. The imagery evokes a setting of death and reflection, with tomb, vault, and churchyard symbolizing the final resting place of the ill-fated lovers. Words like torch and watch suggest a quiet vigil, while flowers and monument imply the tribute and memorialization of Romeo and Juliet’s tragic love. The bustling streets have given way to the solemn stillness of the tomb, where the true cost of the feud is finally laid bare in grief and loss.

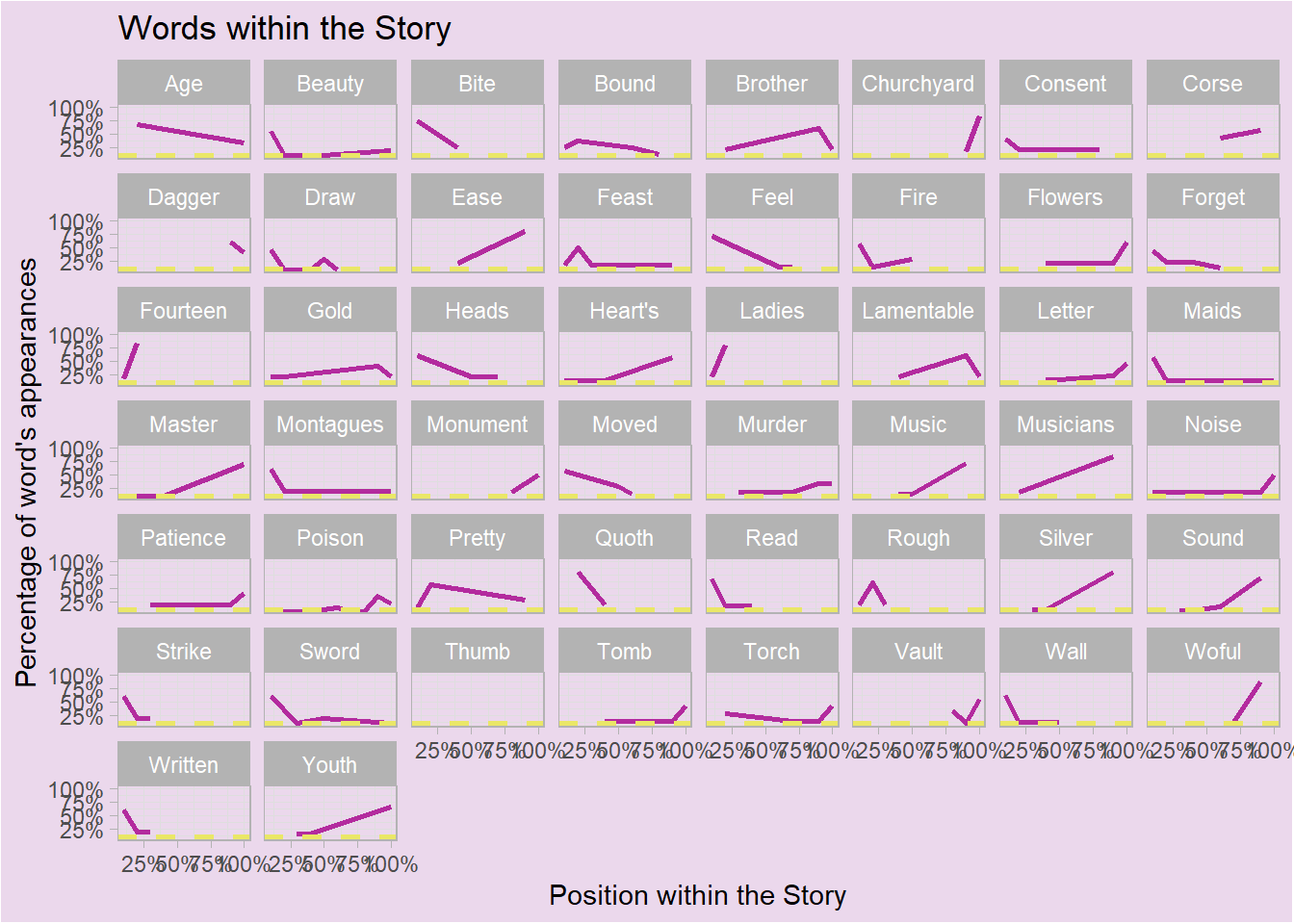

From Conflict to Tragedy: The Changing Language of Romeo and Juliet

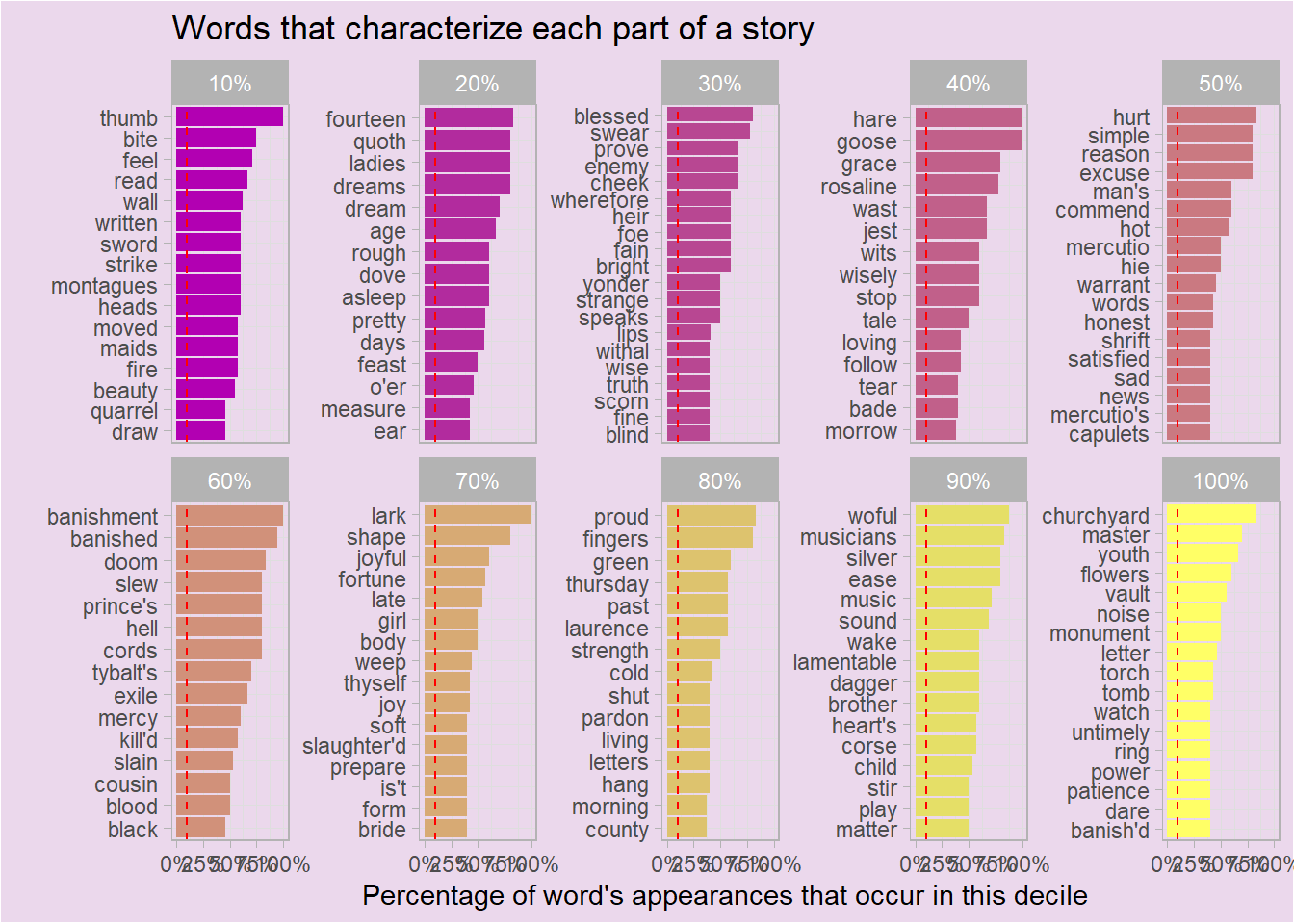

This trend chart illustrates the dramatic evolution of language throughout Romeo and Juliet, with key words plotted based on their frequency and position within the play.

Beginning Words (Conflict and Confrontation):

In the early scenes, words such as Bite, Heads, Maids, Strike, and Sword dominate, reflecting the intense street brawls and public confrontations between the servants of the Montagues and Capulets. These words spike at the start, setting a tone of tension and escalating violence. The high frequency of these terms underscores the environment of hostility that defines the opening scenes of the play.

Transition Words (Love and Emotion):

As the story moves into its middle acts, words like Feast, Feel, and Moved come into play, signaling a shift from physical conflict to emotional intensity. The word Feast, for example, corresponds to the Capulet ball where Romeo and Juliet first meet, while Feel and Moved represent the growing emotional stakes as their love deepens.

Ending Words (Tragedy and Mourning):

Towards the end, the language changes significantly. Words such as Tomb, Vault, Monument, Churchyard, and Torch dominate, marking the shift from conflict to tragedy. These terms reflect the somber setting of the final acts, as Romeo and Juliet meet their fate in the Capulet tomb. The rise in these words illustrates the story’s transformation from chaotic public violence to a private, tragic conclusion.

The chart highlights how Shakespeare masterfully shifts the play’s tone and focus through language. Starting with the aggressive, confrontational words of a violent feud, the play moves towards the quieter, more reflective language of death and mourning. This progression mirrors the journey of Romeo and Juliet—from star-crossed lovers caught in the crossfire of a family feud to tragic figures whose deaths ultimately reconcile their warring families.

decile_count <- romeo_juliet_token %>%

mutate(word_position = row_number()/n()) %>%

group_by(word) %>%

mutate(decile = ceiling(word_position * 10) / 10) %>%

count(decile, word)

trend <- decile_count %>%

inner_join(combined, by = "word") %>%

ggplot(aes(decile, n / number)) +

geom_line(colour = "#B32B9E", linewidth = 1) +

facet_wrap(~ str_to_title(word)) +

scale_x_continuous(labels = scales::percent_format()) +

scale_y_continuous(labels = scales::percent_format()) +

geom_hline(yintercept = .1, color = "#EAE767", lty = 2, linewidth = 1) +

theme(plot.background = element_rect(fill = "#EBD8EC"),

panel.background = element_rect(fill = "#EBD8EC"),

plot.title = element_textbox()) +

labs(x = "Position within the Story",

y = "Percentage of word's appearances",

title = "Words within the Story")

The Words that Shape Romeo and Juliet’s Emotional Journey

This chart illustrates the evolving language of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, highlighting key words that characterize different stages of the play. In the beginning (10%), words like “thumb” and “quarrel” emphasize conflict and tension. As the play progresses (20-30%), romantic terms such as “dream” and “lips” take center stage, reflecting the blossoming love between Romeo and Juliet. By the midpoint (50-60%), darker words like “banishment” and “doom” emerge, signifying rising tragedy. In the later stages (70-100%), words like “woful,” “dagger,” and “churchyard” capture the sorrow and finality of the lovers' deaths. Shakespeare’s language shifts from passion and hope to despair, guiding the audience through a powerful emotional journey.

Each decile has some some words that peak within it.

peak_decile <- decile_count %>%

inner_join(word_averages, by = "word") %>%

filter(number > 4) %>%

transmute(peak_decile = decile,

word,

number,

fraction_peak = n / number) %>%

arrange(desc(fraction_peak)) %>%

distinct(word, .keep_all = TRUE)

## Warning in inner_join(., word_averages, by = "word"): Detected an unexpected many-to-many relationship between `x` and `y`.

## ℹ Row 8 of `x` matches multiple rows in `y`.

## ℹ Row 393 of `y` matches multiple rows in `x`.

## ℹ If a many-to-many relationship is expected, set `relationship =

## "many-to-many"` to silence this warning.

peak <- peak_decile %>%

group_by(percent = fct_reorder(scales::percent(peak_decile), peak_decile)) %>%

top_n(15, fraction_peak) %>%

ungroup() %>%

mutate(word = reorder(word, fraction_peak)) %>%

ggplot(aes(word, fraction_peak, fill = peak_decile)) +

geom_col(show.legend = FALSE) +

geom_hline(yintercept = .1, color = "red", lty = 2) +

coord_flip() +

facet_wrap(~ percent, nrow = 2, scales = "free_y") +

scico::scale_fill_scico(palette = "buda", guide = "none") +

scale_y_continuous(labels = scales::percent_format()) +

theme(plot.background = element_rect(fill = "#EBD8EC"),

panel.background = element_rect(fill = "#EBD8EC"),

plot.title = element_textbox()) +

labs(x = "",

y = "Percentage of word's appearances that occur in this decile",

title = "Words that characterize each part of a story")

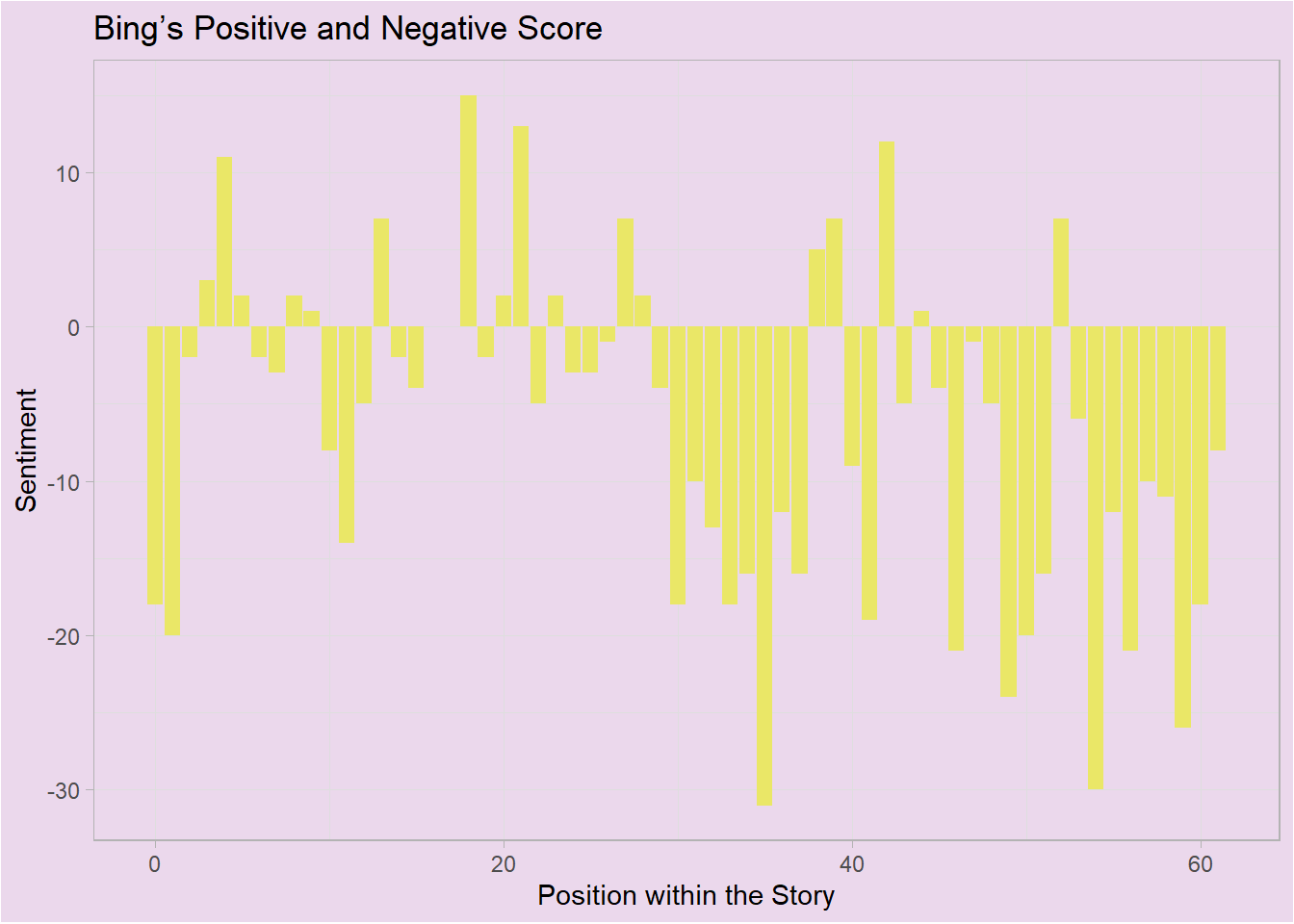

Sentiment Analysis

In conclusion, this Bing sentiment analysis highlights the emotional journey in Romeo and Juliet. While there are brief moments of hope and romance, the overall trend of the play leads to increasing negativity, reflecting the inevitable tragedy. Shakespeare’s language, from hopeful and poetic in the beginning to dark and sorrowful by the end, mirrors the trajectory of the story’s emotional tone.

bing <- get_sentiments("bing")

sent <- romeo_juliet_token %>%

inner_join(bing, by = "word", relationship = "many-to-many") %>%

count(sentiment, index = line_number %/% 50) %>%

pivot_wider(names_from = sentiment, values_from = n, values_fill = 0) %>%

mutate(sentiment = positive - negative) %>%

ggplot(aes(index, sentiment)) +

geom_col(fill = "#EAE767") +

theme(plot.background = element_rect(fill = "#EBD8EC"),

panel.background = element_rect(fill = "#EBD8EC"),

plot.title = element_textbox()) +

labs(x = "Position within the Story",

title = "Bing's Positive and Negative Score",

y = "Sentiment")